CANADA'S FIRST JEWISH MARRANA?

Esther Brandeau of Quebec

(adapted from Lusitania.ca by Manuel Azevedo)

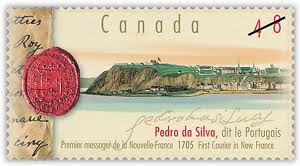

Despite a French prohibition against non-Catholics from settling in its colonies, Portuguese names appear in New France (Quebec) in the early 1700’s; Joseph da Silva of Montreal, a creditor of the government (referred to as “the so-called Portuguese”), Maranda from Bayone (1711) and Jacob Coste (1744), and not to forget Canada's first letter carrier, Pedro da Silva* (1673), born in the heart of the Great Jewish quarter of Lisbon.

However, it is Esther Brandeau who arrived in New France in 1738 that was the first Jewess to immigrate to Canada. Except she was not a youthful twenty-year-old Esther who arrived aboard the ship, the St. Michel, but rather a young man named Jacques la Fangue, her alias. Esther arrived wearing mens' clothes!

Brandeau was arrested upon disembarking. Lacking an appropriate jail, she was detained at the colonial hospital. On September 15, 1738, she appeared before the Marine Commission of Quebec and declared her name to be Esther Brandeau, daughter of David Brandeau (Brandao?), a Jew of St. Esprit diocese, a suburb of Bayonne near Bordeaux in south west France, long known as a haven for “Portuguese merchants”, a euphemism for New Christians (secret Jews) fleeing the Inquisition in Portugal.

The amalgamation of the Spanish and Portuguese crown in 1580 to 1640 facilitated the exodus of Portuguese Jews to France. The Governor of New France, a cousin of the King, reported to the Minister of Colonies that many attempts were made to persuade Esther to abandon her religion, but she refused.

Intendant Hocquart reported, “Her conduct has not been wholly bad but she is so frivolous that at different times she has been both obedient and obstinate with regard to the instruction the priests desired to give her. I have no other alternative than to send her back.”

And so after spending about a year in Canada, Esther was deported back to France on the express orders of the King who also paid for her passage.

*http://www.canadapost.ca/cpo/mc/personal/collecting/stamps/archives/2003/2003_jun_pedro.jsf

A Jewess in New France by Pierre Lasry

I do not doubt that Pierre Lasry accurately depicted the journey of Esther Brandeau as reported in September of 1738, in a verbal report by Varin de La Mare, the Marine Commissioner of Quebec.

I do not doubt that Pierre Lasry accurately depicted the journey of Esther Brandeau as reported in September of 1738, in a verbal report by Varin de La Mare, the Marine Commissioner of Quebec.

We also find the following names of men along with the others already named

FROM

Jewish Women's Archive. "JWA - Jewish Women In Travel - Esther Brandeau." http://jwa.org/discover/infocus/travel/brandeautravel.html (September 1, 2011).

*http://www.canadapost.ca/cpo/mc/personal/collecting/stamps/archives/2003/2003_jun_pedro.jsf

A Jewess in New France by Pierre Lasry

Commentaries by Jean-Marie Gélinas

Translation made from French to English by Jane Lavallee, Palm Springs, CA, USA

Centre Gélinas sur Internet è ( Important notice )

I do not doubt that Pierre Lasry accurately depicted the journey of Esther Brandeau as reported in September of 1738, in a verbal report by Varin de La Mare, the Marine Commissioner of Quebec.

I do not doubt that Pierre Lasry accurately depicted the journey of Esther Brandeau as reported in September of 1738, in a verbal report by Varin de La Mare, the Marine Commissioner of Quebec.During the entire biography, Pierre Lasry wrote magnificently and with much affection about the character and the Jewish identity of Esther Brandeau. In this historical novel, Esther Brandeau, for the first time, emerges from the obscurity to which she was relagated by our historians. At the time of her arrival in New France, Esther Brandeau attracted the attention of the French authorities when she declared that she was a Jewess. Up until that time, the authorities ignored or pretended to ignore the “new Christians” (Jews from Spain and Portugal) who were intermingled with Catholics and Protestants upon their arrival in New France and who wished to escape integration into the European culture. It is true that the new Christians had to declare to French authorities that they were either Catholic or Protestant and had to provide proof before embarkation at the port of La Rochelle to journey to New France. Is it possible that the noble Michel de Salaberry forgot this detail? Or, did he have another reason for shutting his eyes to this matter? This is the question. This is the puzzle.

According to the writings by Varin de La Mare which were found in our archives, there is a curious gap in the facts and there is evidence of a possible complicity that Esther Brandeau benefited by embarking from the port of La Rochelle. We wish to question the reason which caused Esther Brandeau to embark as a passenger on the Saint Michel for New France. Again, why is the only testimony in this record that of Esther Brandeau? Why wasn’t the principal witness in this matter, Michel de Salaberry, interrogated - why was he absent? Why is it that the responsibility of proof in this record rests solely on the shoulders of Esther Brandeau? All the same, is not the captain of his ship, aside from his responsibility to answer to the laws of the King, the sole master on board after God?

Let us examine the declaration made to Monsieur Varin de La Mare by Esther Brandeau in the town of Quebec on the 15th of September 1738. She said that she was twenty years old and that she embarked from the port of La Rochelle on the Saint Michel, which was under the command of Sir Salaberry (Michel de Salaberry). She was a passenger, dressed as a man, under the assumed name of Jacques La Faugue. She added that she was called Esther Brandeau, a Jewess, a merchant from the town of Saint-Esprit in the Diocese of Daxe, near Bayonne, and that she was of the Jewish faith.

She recounted that five years ago, her father and mother put her aboard a Dutch ship, under the command of Captain Geoffroy, which was to sail to Amsterdam and there she would stay with her aunt and brother. The sailboat was broken up (in April or May 1733) on a sand bar near the dunes of Bayonne and that she was fortunately saved by one of the members of the crew. She was taken away by the widow Catherine Churiau who lived in Biarritz. Fifteen days later, dressed as a man, she left for Bordeaux, and going by the assumed name of Pierre Alansiette, she embarked as a cook on a sailboat for Nantes, which was under the command of Captain Bernard. She came back to Bordeaux on the ship’s return journey. She then embarked again as a cook on a Spanish ship, under Captain Antonio, which was leaving for Nantes. Upon arriving in Nantes, she deserted and went to Rennes where she worked as a male apprentice to a tailor named Augustin and she remained there for six months.

Varin de La Mare asked Esther Brandeau to explain the reason why she disguised herself as a man for five years. She said that after being saved from the shipwreck and arriving in Bayonne, she found herself in the home of Catherine Churiau, as indicated above, where she was made to eat pork and other meats which were forbidden by her Jewish faith. She made a vow at that time not to return to her father and her mother in order to enjoy the same liberties as Christians.

In Versailles, this deposition met with suspicion: “I do not know if we should entirely have faith in this declaration made by the named Esther Brandeau who last year, disguised as a boy,

embarked upon the ship Saint-Michel and said that she was a Jew.” Wrote the minister to the Intendant Hocquart.

Source consulted:

- Denis Vaugeois, Les Juifs et la Nouvelle France, Collection 17 - 60, Les Editions Boréal Express, Trois-Rivières.

New France was never a penal colony:

During all of it’s history, New France was never a penal colony. It was the colony of New Orleans which held that function for France. but never at the level of the English colonies, which later became the United States. If New France had been a penal colony, America would be French!

In 1988, while I was researching in the Maritime Archives in La Rochelle, France, I found a document from the 17th century - it was a regulation which was the law at the port of La Rochelle which clearly established the will of the King of France. It formally prohibited all port authorities and commanders of ships from recruiting itinerants and vagabonds and forbidding them to sail to New France. All persons, without exception, who embarked on ships leaving for New France, had to have their status verified by the port authorities including the ship’s captains prior to sailing. The royal regulation was formal and all persons had to be identified and be in possession of the required papers for embarkation.

Not everyone who wished to embark was allowed to go to New France! Those who did not follow the regulations, were subject to Royal justice One can always consult the document in the Archives in La Rochelle, France. Moreover, the cost for each of the ship’s passengers during that epoch was a fortune. Do not forget this!

Sources consulted:

- Archives Maritimes of La Rochelle, France.

Sieur Michel de Salaberry was a noble, he was the son of Martin and Marie Maichelance, of Saint-Vincent-de-Cibour, diocese of Bayonne, Gascony. In 1737 at La Rochelle, he was named Captain of the ship, Saint-Michel, in which he made the ship’s only journey to New France. Michel de Salaberry was legally married, because previously, he came to Quebec in 1735 where he married on the 14th of May in that same year, Marie-Catherine Rouer de Villeray She was the daughter of Augustin Rouer de Villeray, Sieur de la Cardonnière and of Marie-Louise Pollet (and the granddaughter of Louis Rouer de Villeray de la Cardonnière, the civil and criminal lieutenant in New France who was the son of Jacques Rouer de Villeray, valet to the Queen of Notre-Dame en Grève, town of Amboise, in the Diocese of Tours; buried on the 7th of December 1700 in the church in Quebec).

Sieur Michel de Salaberry lived in Quebec during the time when his wife, Marie-Catherine Rouer de Villeray gave him two daughters and she died suddenly on the 26th of August 1740.

Children:

- Marie-Angelique, b. 22 November 1735

- Michel, b. 7 September and buried 13 November 1736

- Angelique and Denise, b. On the 5th and buried on the 6th of May 1737

- Louise-Geneviève, b. 2 June 1739: Nun (Sainte-Catherine), vows taken on 3 June 1755 buried on 2 December 1823 at the Hôpital Général in Québec.

A little while after the death of his wife Marie-Catherine Rouer de Villeray, Michel de Salaberry returned to France. According to the archives, from the time of the adventures of Ester Brandeau in New France, Michel de Salaberry did not assume command of any merchant vessel. Coincidence? It wasn’t until 1745, that he returned to this land (Quebec) in order to transmit the Orders of the King to the Governor, the Marquis de Beauharnois. When Quebec welcomed him again in 1750, we find him as an officer on the frigate “L’Angleza”.

On the 30th of July 1750 in Beauport, Michel de Salaberry was married for a second time to Madeleine-Louise Juchereau Duchesnay de Saint-Denis, the daughter of the Seigneur of Beauport. It was only in 1752 that we find him as the captain of the Royal vessel. “Le Chariot Royal”.

It was is 1760, after the conquest, when he finally left for France where his wife, Madeleine-Louise Juchereau Duchesnay de Saint-Denis died three or four months later. During his stay in

Canada, his wife gave him one son, Louis-Ignace-Michel, who was born on the 5th of July 1752. In order for the latter to have the power to claim the estate inherited from his mother, he was entrusted to his maternal grandparents in Canada, who made him study at the seminary in Quebec, studies which he afterwards completed in France.

Louis-Ignace-Michel de Salaberry returned to Canada at the age of 22. In 1755, as the Captain of Militia, he recruited volunteers who joined the regular army to repel the invasion of the Americans. He married in 1778. He married Françoise-Catherine Hertel, the daughter of Joseph Hertel, Seigneur of Pierreville. With his wife, he settled in Beauport in the house which once belonged to Robert Griffard. Charles-Michel (the future hero of the battle of Casteauguay) was born ten months later. Three other children followed, but they died at the time of their birth.

As we have come to see, Michel de Salaberry came from a family of noble ancestors. One can trace this noble family back to the 9th century. A descendant of the King of Navarre during this time, founded the dynasty of the Viscounty of Sault from which the Salaberry line descended. In 1099, an ancestor of the de Salaberry family accompanied Godefroy de Bouillon in the Crusade. During the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, the de Salaberry family distinguished themselves in the service of the Kings of France. One of two was Abbot Louis-Charles-Victoire-Vincent de Salaberry, who was the counsel to the State in 1758. Another one, Charles-Victor-Vincent de Salaberry was a victim of the French Revolution in 1794.

In 1746, the de Salaberry family split up into two branches - the oldest and the youngest. It was the youngest branch that settled in Canada.

Reference Sources:

- The notebooks of the Seigneurie of Chambly, volume III, number 2 September 1981, No. 6, by Armand Auclair.

- Dictionaire Généalogique des Familles Canadiennes, Mgr, Cyprien Tanguay

- Dictionaire des Canadiens Français, Institut Drouin

As we have seen, it is difficult to explain how Esther Brandeau was able to embark on the St-Michel by herself, without any help and without the complicity of the Captain, or of the port authorities. Who was the accomplice who was hidden in this dossier? Possibly a love story? Why not?

As we uncover what concealed this historic adventure of Esther Brandeau, we are left to wonder about the way in which Sieur Varin de La Mare , the Royal Commissioner of the Navy in Quebec, carried out this investigation. We can better understand the involvement of the King, who paid the return passage for Esther Brandeau.

How are we to understand the history of Esther Brandeau, a subject that has been taboo for a long time in Quebec. Will the secret of Esther Brandeau and Michel de Salaberry remain buried for a long time in out collective memories?

Whatever were the hidden motives of this history, today it is clear that the adventures of Esther Brandeau in New France could not have been possible without an accomplice. The lack of testimony in this document of the principal witness, Michel de Salaberry, seems anomalous to us.

The Town of St-Esprit: (other considerations)

Abraham Andrade, citizen of the town of St-Esprit, guided by the sentimentality of his youth, was driven, so to speak, to be put at the head of the judicious movement of the French Revolution in 1789. Thinking that he would not find any resistance, and also to quickly control the situation, he insisted that the town of St-Esprit, which was made the capitol, be dedicated to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and that this name should replace the too Christian name of their town.

At the time of the Revolution, all of the citizens of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (formerly the town of St-Esprit) were bound by the rules to declare their wealth to the French State and a board was formed which charged the fortunes that one could possess. The powerful Jewish families were all registered and taken together, their fortunes amounted to the sum of 7,500,000 pounds. The sum of 1,290,000 pounds was attributed to the non-Jews in the same locality.

List of the Jewish citizens of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (town of St-Esprit) and Grande Redoute

Leon Lafite | 100,000 pounds | widower without children |

The widow of Moyse Henriques de Castro | 100,000 pounds | widow without children |

David Alexandre | 60,000 pounds | married with wife |

Lassarade | 70,000 pounds | married with wife, 5 children, father-in-law and mother-in-law having a very lucrative business |

Samuel de Jacob Louis Nounés | 50,000 pounds | married with wife |

Marq foy father | 50,000 pounds | married with wife, 1 child |

Delvaille, father and son | 150,000 pounds | their wives, 6 children |

Joseph Desirat, baker of pastries | 60,000 pounds | widower, 2 children |

Jacob Henriques de Castro | 120,000 pounds | mother, wife, aunt, 6 children |

Bernard the elder | 50,000 pounds | widower, 1 child |

Ballas and Son, baker of bread | 40,000 pounds | same household, their wives |

Lévy the elder | 60,000 pounds | widower, 4 children |

Lévy the younger | 50,000 pounds | bachelor |

Dominique Larrieu | 100,000 pounds | wife, 4 children |

Laforcade | 200,000 pounds | widower without children |

Mendez France | 150,000 pounds | wife, mother, 4 children, not including their property in America |

Céfourcade | 50,000 pounds | wives, 4 children |

Jean-Baptiste Gassis | 40,000 pounds | wives, 8 children |

Gignan | 50,000 pounds | married with wife |

Laconne | 100,000 pounds | married with wife, 8 children |

Forgue, notary | 40,000 pounds | married with wife |

Benjamin Ferro and mother-in-law | 45,000 pounds | married with wife and mother-in-law, 1 child |

Samuel de Samuel Nounés | 70,000 pounds | married with wife |

Widow Castro and youngest son | 100,000 pounds | with 6 children |

Dormillier, director | 200,000 pounds | 6 children |

Nunés brothers | 200,000 pounds | 2 wives, 6 children, 2 housekeepers |

Abraham Nunés | 150,000 pounds | his wife and 2 housekeepers |

Delvaille the elder | 150,000 pounds | wives, 8 children |

David Salzedo | 40,000 pounds | wives, 4 children |

Furtado the young | 180,000 pounds | married with wife |

Abraham Louis Nounés | ||

Jullian | ||

Daniel Fernandez Patto | 70,000 pounds | married with wife, 4 children |

Moyse Fernandez Patto | 100,000 pounds | widower, 1 child |

Benjamin Nunés | 50,000 pounds | married with wife, 6 children |

Desclaux | 40,000 pounds | wife, mother, 1 child |

Duffau, marshal | 40,000 pounds | married with wife, 2 children |

Lartigue | 50,000 pounds | married with wife |

Gassané | 60,000 pounds | mother and son |

Labrouche | 150,000 pounds | married with wife |

Abraham Fernandez Patto and Margueridon Montespan were respectively president and president of the community of the town of St-Esprit, which became during the Revolution, as we have said, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Grande Redoute. It seems that there is one president for the men and another president for the women at the time of the French Revolution.

We also find the following names of men along with the others already named

Abraham Fernandez Patto - Larre - Moffre - Patto, jeune - Isaac D'Avron Rodrigue - Dominic Larrieu - Josué Patto - Baptiste Laporte - Abraham de Jacob Louis Nunés - Valery the youngest - Estoup

The following are names of the women:

Margueridon Montespan - Victoire Tavarez - Lacorne - Céfourcade - Sara Olivera - Judith Louis Nunez - Thérèse Bagnères - Rosette Silva - Larre - Chanda - Desbarbet.

Other names:

Bergez, Master of the Community (probably the Rabbi) - Gabriel P. Souarez - J. Léon - Valéry - Dandrade - Bernal - Tavarez - Isaac Gomez Baïs - Moïse Brandam, fonction de hasan - Ester Morais - Samuel Baruch Cavaillo - Jeosua Los Rios Espinosa - Ester Leon - Rachel de Herera - Jacob Frois - Elie Pechaud - Sara Rachel Rodrigue - Ester Baïs - Rebeka Dacosta - etc...

Consulted Sources:

- Etablisement des Juifs à Bordeaux, Francia De Beaufleury

- Histoire des Juifs à Bordeaux, Théophile Malvesin

- Bibliothèque Nationale à Paris

Researcher: Jean-Marie Gélinas

13 August 2001

FROM

Jewish Women's Archive. "JWA - Jewish Women In Travel - Esther Brandeau." http://jwa.org/discover/infocus/travel/brandeautravel.html (September 1, 2011).

Eighteenth century woman Esther Brandeau's (c. 1718-?) desire for travel and adventure was so strong that she broke the restrictions of gender and the laws of the land to leave her home in La Rochelle, France, for the Americas. She arrived in Canada by a circuitous route. Her parents had sent her to live with relatives in Amsterdam. When her ship was wrecked on route to the Netherlands, she chose her own path, determining to "enjoy the same liberty as the Christians." She worked a series of different jobs under assumed male names in various parts of France. In 1738, when she was only 20, she became "Jaques La Fargue," the cabin boy on the "San Michel," a ship sailing to Quebec. It was as "Jacques" that Esther became the first Jew known to set foot in Canada.

Quebec City, 18th century, from the UC Davis History Project.

Esther's entry into Canada was illegal, since it was Canadian government policy to exclude all Jews and Huguenots. Unfortunately, Esther's gender and background were revealed on her arrival in Quebec, when her shipmates made "the remarkable discovery that the comely, spirited youth with such refined manners was in fact not "Jacques" but Esther."

Once discovered, Esther was arrested. She quickly became an administrative nightmare for the French-Canadian authorities, largely because she rejected the ministrations of Catholic priests, adamantly refusing to convert to Christianity. She asserted that she had left her home and dressed as a boy in order to have the same rights as Christian men, but still held fiercely to her Jewish background.

After years of legal wrangling between the governments of Canada and France, Esther was deported, and she vanished from the historical record. Her story shows the lengths eighteenth-century Jewish women had to go to in order to fulfill their dreams and explore the world beyond (and even within) their native lands.

Sources and excerpts for this page were drawn from Shalom Quebec, a website created for the 400th birthday of Quebec, highlight Jewish contributions to the city and Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Special thanks to Simon Jacobs of the Shalom Quebec project for his help.

How to Cite This Page

Jewish Women's Archive. "JWA - Jewish Women In Travel - Esther Brandeau." (September 1, 2011).

Jewish Women's Archive. "JWA - Jewish Women In Travel - Esther Brandeau."